NEW BOOK! Reading Group: “The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman” by Davi Kopenawa & Bruce Albert. Online | Portuguese & Spanish | Supported by CLAREC and Universidade Emancipa | Click here to register.

É com grande alegria que te convidamos para mais uma jornada de reflexões e diálogos no nosso Grupo de Leitura. A próxima leitura será o livro “A QUEDA DO CÉU” de Davi Kopenawa & Bruce Albert. Gostaríamos de convidá-la para abrilhantar o nosso encontro!

Os encontros serão online, sempre às quartas-feiras, das 19:00 às 20:00 (horário de Brasília), conforme a agenda abaixo:

Cronograma:

Facilitação: Nina Lys, Marco Túlio & Alexandre da Trindade

Abertura: Teatro Oficina

Inscrição: https://forms.gle/75KWkfKDAZ3Eut5A6

📍17 de janeiro de 2024 (quarta-feira) às 19 horas (online)

Leitura: Prólogo & Capítulo 1 – “Desenhos de escrita”

Convidades: Roderick Himeros & Marcelo Drummond (Teatro Oficina) + Lilly Baniwa & Casé Angatu

📍31 de janeiro de 2024 (quarta-feira) às 19 horas (online)

Leitura: Capítulos 7 & 8 – “A imagem e a pele” e “O céu e a floresta”

Convidada: artista indigena (a ser confirmado)

📍06 de março de 2024 (quarta-feira) às 19 horas (online)

Leitura: Capítulos 10 & 12 – “Primeiros contatos” e “Virar branco?”

Convidada: antropóloga (a ser confirmado)

📍20 de março de 2024 (quarta-feira) às 19 horas (online)

Leitura: Capítulo 14 – “Sonhar a floresta”

Convidada: educador/a indígena (a ser confirmado)

📍03 de abril de 2024 (quarta-feira) às 19 horas (online)

Leitura: Capítulos 22, 23 & 24 – “As flores do sonho”, “O espírito da floresta” e “A morte dos xamãs”

Convidada: xamã (a ser confirmado)

Sobre o Livro:

KOPENAWA, Davi & ALBERT, The falling sky: words of a yanomami shaman, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2013

Tradução: Beatriz Perrone-Moisés

Audio Livro: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EZNhgxeD79E&list=PLShqadQrMjWgtnDpXosZbOM8GumC2QafI

Este livro é composto de três partes:

A primeira (“Devir outro”) relata os primórdios da vocação xamânica e, em seguida, a iniciação de Davi Kopenawa sob a orientação do sogro. Descreve ainda sua concepção da cosmologia e do trabalho xamânico yanomami, com base no saber adquirido graças à escuta dos antigos xamãs que o iniciaram.

A segunda parte (“A fumaça do metal”) trata do encontro — seu e de seu grupo, e depois de seu povo — com os brancos. Abre com os rumores xamânicos que precederam os primeiros contatos e termina com a irrupção mortífera dos garimpeiros, depois de passar pela chegada dos missionários e pela abertura da estrada Perimetral Norte.

A terceira parte (“A queda do céu”) evoca, ao contrário, o périplo realizado por Davi Kopenawa para denunciar o extermínio dos seus e a devastação da floresta, saindo da sua comunidade para visitar grandes cidades, primeiro no Brasil, depois na Europa e nos Estados Unidos. Este último relato, construído na forma de uma série de viagens xamânicas, é entremeado com meditações comparativas a partir de uma etnografia crítica de certos aspectos de nossa sociedade, e desemboca numa profecia cosmoecológica sobre a morte dos xamãs e o fim da humanidade.

Sobre os autores:

Davi Kopenawa é xamã e líder político do povo Yanomami, presidente da Hutukara Associação Yanomami, ativista na defesa dos povos indígenas e da floresta amazônica, além de autor, roteirista, produtor cultural e palestrante. É uma das lideranças intelectuais, políticas e espirituais mais importantes no panorama contemporâneo de defesa dos povos originários, do meio ambiente, da diversidade cultural e dos direitos humanos, com reconhecimento nacional e internacional. É também autor da obra A queda do céu – palavras de um xamã yanomami (2010), em coautoria com o antropólogo francês Bruce Albert. Fonte: https://ea.fflch.usp.br/autor/davi-kopenawa

Bruce Albert é um antropólogo francês nascido no Marrocos, em 1952. É doutor em antropologia pela Université de Paris X-Nanterre e pesquisador sênior do Institut de Recherche pour le Développement. Começou a trabalhar com os Yanomamis do Brasil em 1975.

*****

Se você tem interesse em participar dessa leitura conosco, por favor preencha este breve formulário para receber mais informações e o link para acessar os encontros. Se você tiver dificuldade para acessar o livro entre em contato conosco: clarec.cam.edu@gmail.com

Este convite é aberto à qualquer pessoa, então fique à vontade para repassá-lo para seu ciclo de contatos.

Outras informações sobre a dinâmica do Grupo de Leitura serão enviadas pelas organizadoras da próxima sessão apenas para os registrados neste novo formulário.

Também te convidamos para se juntar ao nosso grupo de WhatsApp (opcional) – https://chat.whatsapp.com/KWxH2lhzxY616iuQIJYmUY

Abraços fraternos,

Nina Lys, Marco Túlio, Alexandre da Trindade & Grupo de Leitura,

com apoio de CLAREC e Universidade Emancipa

Past Reading Groups

NEW BOOK! Reading Group: “THE POLITICAL WRITINGS FROM ALIENATION AND FREEDOM” by Frantz Fanon. Online | Portuguese & Spanish | Supported by CLAREC and Universidade Emancipa | Click here to register.

CLAREC @clareccam & Universidade Emancipa @uemancipa convidam para mais uma jornada de reflexões e diálogos no nosso Grupo de Leitura! A próxima leitura será o livro “ESCRITOS POLÍTICOS” de Frantz Fanon”.

Os encontros serão online e quinzenais, sempre às quartas-feiras, das 19:00 às 20:00 (horário de Brasília), conforme a agenda abaixo:

📍 23 de agosto de 2023: PREFÁCIO, INTRODUÇÃO & DEBATE YOUTUBE BOITEMPO – “Por que ler Fanon?” | Com Deivison Faustino, Priscilla Santos e Geni Núñez

📍 06 de setembro de 2023: pp. 44-96

📍 20 de setembro de 2023: pp. 97-130

📍 04 de outubro de 2023: pp. 131-177

📍 18 de outubro de 2023: pp. 178-224

Se você tem interesse em participar dessa leitura conosco, por favor preencha o formulário para receber mais informações e o Zoom link para acessar os encontros.

Este convite é aberto à qualquer pessoa, então fique à vontade para repassá-lo para seu ciclo de contatos.

Abraços fraternos,

Grupo de Leitura, com apoio de CLAREC e Universidade Emancipa

NEW BOOK! Reading Group: “THE WRETCHED OF THE EARTH,” Frantz Fanon. Online | Portuguese & Spanish | Supported by CLAREC | Click here to register.

NOVO LIVRO! Grupo de Leitura: “OS CONDENADOS DA TERRA”, Frantz Fanon

[NEW BOOK! Reading Group: “THE WRETCHED OF THE EARTH,” Frantz Fanon – The meetings will be in Portuguese/Spanish. If you wish to organize meetings in English, please contact us at clarec.cam.edu@gmail.com]

É com grande entusiasmo que te convidamos para mais uma jornada de reflexões e diálogos no nosso Grupo de Leitura. A discussão deste livro começará na QUARTA-FEIRA, 31 de maio das 19:00 às 20:00 Brasília (23:00 UK), de maneira online via Zoom.

Se você tem interesse em participar dessa nova leitura conosco, preencha o formulário para receber o link de acesso. Este convite é aberto, então fique à vontade para repassá-lo para seu ciclo de contatos.

📌 Encontros: Quartas-feiras, 19:00 (horário de Brasília)ONLINE & gratuito – em português & espanhol.

* 31/mai: prefácio & documentário “Sobre a violência” de Göran Olsson

* 14/jun: Capítulo 1

* 28/jun: Capítulo 2 & 3

* 12/jul: Capítulo 4

* 26/jul: Capítulo 5 & Conclusão

Inscrição: bit.ly/fanon_leitura O link Zoom será enviado para os registrados.

Sobre o livro:

“OS CONDENADOS DA TERRA”, Frantz Fanon

Os condenados da terra é o ponto culminante de uma obra radical e incontornável abreviada pela morte precoce do psiquiatra martinicano Frantz Fanon, um dos pensadores mais revolucionários do século XX. Ao analisar a situação colonial, Fanon tensiona política, sociedade e indivíduo, demonstrando de forma clara as estratégias e efeitos do poder dominante ― o resultado da opressão é raiva, dor e loucura. Com isso, o autor desmonta a lógica colonial europeia ― branca, brutal e racista ―, e propõe uma “descolonização do ser”, afirmando: “É preciso mudar completamente, desenvolver um pensamento novo, tentar criar um homem novo.” Só assim é possível criar um mundo realmente humano, onde a massa deserdada de homens e mulheres dos países colonizados e pobres ― os condenados da terra ― sejam os inventores de sua própria vida.

Acesse o formulário para mais informações e inscrição.

Vamos junt@s?!

Abraços fraternos,

O Grupo de Leitura é apoiado por CLAREC (https://clarec.org)

NEW BOOK! 🌱 Reading Group: “FUTURO ANCESTRAL” by Ailton Krenak • Friday, March 10 at 09:00 (Brasília) • Online • Portuguese & Spanish | Supported by CLAREC | Click here to register.

It is with great enthusiasm that we invite you to another journey of reflections and dialogue in our Reading Group. The discussion of this book will take place on March 10 from 09:00 to 10:00am Brasília (12:00 UK), Online via Zoom.

If you are interested in participating in this new reading with us, please fill in the form to receive the access link. This is an open invitation, so feel free to pass it on to your network.

About the book:

Futuro Ancestral

by Ailton Krenak

Ailton Krenak provokes us with the radicalism of his insurgent thinking, which demolishes common sense and invokes amazement. The idea of the future sometimes haunts us with apocalyptic scenarios. At other times it presents itself as a possibility of redemption, as if all the problems of the present could be magically solved later. In both cases, illusions keep us away from what is around us. In this new collection of texts, produced between 2020 and 2021, Ailton Krenak says: “The rivers, those beings that have always inhabited the worlds in different forms, are the ones who suggest to me that, if there is a future to be envisaged, that future is ancestral, because it was already here.”

Author: Ailton Krenak

Organizer: Rita Carelli

Cover: Alceu Chiesorin Nunes

Publisher: Companhia das Letras

To buy the book access: https://www.companhiadasletras.com.br/livro/9786559211548/futuro-ancestral

Let’s go together!

With very kind regards,

This Reading Group is supported by CLAREC and University

by Dr. Teresinha Aparecida Del Fiorentino1

O livro apresenta 5 textos: (i) Saudações aos Rios; (ii) Cartografias para depois do fim; (iii) Cidades, pandemias e outras geringonças; (iv) Alianças afetivas; (v) Corações no ritmo da terra.

O título do livro é intrigante e faz pensar. Krenak diz que o futuro é ancestral, querendo dizer que tudo que nos rodeia sempre( desde um passado remoto ) esteve aí, está agora e estará no futuro. Nós, seres humanos, é que somos transitórios e usufruímos desta terra que nos cerca por um certo tempo e ela vai permanecer após morrermos, abrigando as futuras gerações. Daí a nossa responsabilidade em não estragar o meio ambiente para que os homens do futuro possam viver nele. E esse futuro irá conter todo o passado mais as nossas ‘contribuições’, daí a expressão ‘futuro ancestral’.

O texto “Saudações aos Rios” é extremamente oportuno neste momento em que é escancarado ao público o massacre sofrido pelos Yanomami, cujas terras são invadidas principalmente por garimpeiros que poluem os rios com mercúrio e pelas madeireiras que desmatam as florestas.

Krenak analisa as visões contraditórias das pessoas que acham natural considerar um rio distante sagrado enquanto destroem o rio que passa perto delas: “Eu acho engraçado que tem gente que aceita com naturalidade considerar um rio sagrado desde que ele esteja lá na Índia, e saiba de cor que ele se chama Ganges, enquanto ousa saquear o corpo do rio ao lado, cujo nome desconhece, para fazer resfriamento de ciclos industriais e outros absurdos”( p.20 ).

Ele menciona também os rios que cortam as grandes cidades transformados em esgotos e os que correm nos cerrados e florestas flagelados e só vistos como potenciais energéticos para construção de barragens ou como fornecedores de água para a agricultura e a pecuária. E ele alerta: “Acontece que que ao transformarmos água em esgoto ela entra em coma, e pode levar muito tempo para que fique viva de novo. O que estamos fazendo[…] é acabar com a nossa própria existência. Elas( as águas ) vão continuar existindo aqui na biosfera e, lentamente, vão se regenerar, pois os rios têm esse dom. Nós é que temos uma duração tão efêmera que vamos acabar secos, inimigos da água, embora tenhamos aprendido que 70% do nosso corpo é formado por água. Se eu desidratar inteiro vai sobrar meio quilo de osso aqui, por isso eu digo: respeitem a água e aprendam a sua linguagem”( pp. 26-27 ).

“Cartografias para depois do fim” nos deixa meio confusos no início mas acaba oferecendo clareza ímpar no final, defendendo as diferenças que nos enriquecem e garantem a nossa liberdade.

Ele começa mostrando as diferentes narrativas sobre a origem do universo( “…no princípio era a folha…”, “…no princípio era o verbo…” ) “tão bonitas que conseguem dar sentido às experiências singulares de cada povo em diferentes contextos de experimentação da vida no planeta”( pp. 32-33 ).

Krenak aproveita para destacar os estragos que o capitalismo instigador de disputas (especulação imobiliária, ocupação de territórios indígenas, desertos causados pelo pasto) provoca e a aventar a possibilidade de resgatar a vida existente no passado, com todo o esplendor do retorno das plantas, insetos, répteis, animais e fungos pela ação dos indígenas ao retornarem às terras que lhes foram roubadas.

Ele compara a resistência indígena ao movimento do WATU( Rio Doce) que, sendo “um corpo d’água de superfície[…], ao sofrer uma agressão, teve a capacidade de mergulhar na terra em busca dos lençóis freáticos profundos e refazer sua trajetória”( p. 36 ).

Chama a era em que vivemos de “capitaloceno”, afirmando que o capitalismo desenfreado fará da Terra um lugar inabitável, como o corpo do rio assolado pela lama. Refere-se à invasão dos resíduos de plástico que não só se encontram nas barrigas dos peixes mas também já podem ser encontrados nas barrigas dos bebês que nascem. Destaca que “o capitalismo quer um mundo triste e monótono em que operamos como robôs”( p. 38 ). E afirma que não podemos aceitar isso. A solução para ele seria promover a aproximação homem-natureza, fazendo cada um se sentir parte da Terra( costume do povo Kuna, do Panamá, de identificar o corpo de cada criança nascida com um árvore local, fazendo os bosques passarem a ser pessoas, provocando a identificação da comunidade com a natureza que a rodeia/ a crença do corpo feito de barro da tradição do povo Tukano, do alto Rio Negro, na região amazônica, levando a crer que não existe fronteira entre o corpo humano e os outros organismos que estão ao seu redor ) ( p. 39 ).

Krenak afirma que quando fala em adiar o fim do mundo não está falando deste mundo capitalista em colapso. Coloca-se contra a convergência política vista como conciliação( “Ah, para a gente se entender como nação, vamos todos fazer de conta que não houve genocídio”, p. 42 ). Ele diz que, ao contrário, devemos nos insurgir, afirmar que não somos todos iguais e valorizar as nossas diferenças, não como confronto mas por respeito às peculiaridades de cada um. Devemos usar o que o Nêgo Bispo chama de CONFLUÊNCIAS, que “evoca um contexto de mundos diversos que podem se afetar”( pp. 40-41 ). É a articulação das convergências e divergências analisada de forma crítica. E conclui: “… as confluências não dão conta de tudo, mas abrem possibilidades para outros mundos”( p. 42 ). Confluência seria, portanto, o aproveitamento dos pontos de encontro e desencontro não para forçar uma conclusão unificada, mas para buscar alternativas diferenciadas, de preferência transformadoras da realidade.

Voltando ao título deste texto, ele usa a palavra “cartografias” para substituir a palavra ‘cartografia’, que usamos hoje, pensando no momento em que a ideia unificadora for superada e a desigualdade for valorizada. Daí o título ‘Cartografias para depois do fim’.

Em “Cidades, pandemia e outras geringonças”, Krenak começa questionando a ideia de que o sofrimento ensina alguma coisa e criticando o uso abusivo do ambiente virtual e a crença na ideia de que o capitalismo não vai acabar.

A seguir, compara a vida nas grandes cidades com a vida na floresta e mostra que os brancos enxergam a floresta como algo ameaçador, de onde pode sair um lobo, um lobisomem ou um bicho qualquer para nos atacar. E até as pestes podem advir dela, referindo-se à crença de que a Covid-19 possa ter se originado de um bicho selvagem. Assim, as pessoas dentro das cidades sentem-se protegidas do que fica fora, sejam eles bichos selvagens, indígenas, quilombolas, ribeirinhos, beiradeiros( p.53 ). E essas metrópoles, invadidas pela indústria e pela produção, exigem a produção de energia e a fabricação de inúmeras máquinas que praticamente constituem extensões dos corpos das pessoas, poluindo tudo. E ainda mais: os humanos acham que podem comprar tudo e não querem morrer nunca. Para Krenak , a cidade reflete a tentativa de conquistar a eternidade.

Ele critica a saída em massa das pessoas do campo em busca das cidades onde irão passar fome. Acusa o capitalismo, citando o agronegócio, as hidrelétricas como agentes da expulsão dos moradores do campo. Culpa engenheiros, arquitetos, urbanistas, incorporadoras, especuladores imobiliários, empreiteiras, vereadores pela expansão das cidades, ajudando a destruir a natureza. O consumismo, o uso de matérias primas não renováveis como o ferro, o cimento, a pedra empregados na arquitetura moderna provocam um dano irreparável. E ele conclui que “ a gente devora montanhas e engole o subsolo da Terra para erguer cidades”( p. 59 ).

Também acusa os ocidentais de terem uma cultura sanitarista que os faz desrespeitar, por exemplo, a promiscuidade das cidades da Índia e a pensar “que o que não é cidade, o que não é limpinho, a gente elimina do mapa.[…] a floresta, os bosques, os ecossistemas vivos, com sua capacidade de produzir vida e também vírus vão se constituir em lugares que devem ser cercados para não contaminarem as cidades”( p. 61 ).

E ele pergunta: “ O que estou dizendo parece absurdo?”( p. 62 )

Respondendo: à primeira vista sim, mas vale a pena considerar alguns aspectos que Krenak levanta mesmo que ainda não tenhamos respostas satisfatórias:

– por que o homem branco não respeita as árvores, destruindo-as sem sequer saber os nomes delas?

– como conviver com as comunidades humanas que vivem nas florestas sem enxergá-las como bárbaras, primitivas?

– por que colocar asfalto e cimento em tudo?

– por que cobrir os córregos que atravessam as cidades?

– como trazer a natureza para o centro das cidades transformando-as por dentro?

– por que não deixar nossos quintais cheios de mato?

– por que não considerar o valor das habitações indígenas que se integram no habitat, respeitando seu entorno?

– por que a cidade moderna não tolera o comum, o simples, e o hostiliza?

Em “Alianças afetivas”, Krenak contrapõe os conceitos de cidadania e florestania. Diz que cidadania faz parte do repertório do homem branco, enquanto florestania surgiu num contexto regional de luta dos povos que vivem na floresta, mais especificamente Chico Mendes, seringueiros e indígenas, como reação à intenção do governo brasileiro fragmentar as grandes extensões de florestas no sul do Amazonas e no Acre, abrindo estradas, levando colonos e oferecendo lotes para quem já estava lá.

Junto com Chico Mendes, levantaram-se os indígenas que viviam em reservas coletivas e os seringueiros vindos do Nordeste desde o final do século XIX e que, após algumas gerações dentro da floresta, queriam viver como índios. E criaram a ALIANÇA DOS POVOS DA FLORESTA, em 1980, com a participação de Ailton Krenak. Queriam construir a florestania, não estavam sequer interessados em ter CPF. A experiência que tinham com os patrões latifundiários( geralmente não vivendo na área ) que se apossavam dos seringais e exploravam as terras, os indígenas e não indígenas ( submetidos a condições de trabalho escravo ) foi a grande motivadora. Como Krenak acentua: “Ao nos insurgirmos para eliminar a figura do patrão, foi possível nos associarmos”( p. 79 ). E ele evidencia a dificuldade de construir um sistema de uso coletivo da terra onde “o cancro do capitalismo só admite propriedade privada”( p. 78 ).

Krenak afirma que “a Aliança dos Povos da Floresta[…] nasceu da busca por igualdade nessa experiência política”( p. 79 ). Então começa a questionar: política vem de pólis, o mundo da cultura, e o mundo pelo qual ele, Krenak, se interessa é o da natureza, visto como selvagem pela cultura ocidental. Ele acredita que os seres que não são da pólis podem imaginar mundos diferentes. Assim começou a se perguntar o que iria virar a Aliança dos Povos da Floresta: um sindicato? Um partido? “Alianças políticas nos obrigam a uma igualdade que chega a ser opressora, mesmo aquelas que admitem a existência da diversidade”( pp. 81-82 ). Assim, após mais de vinte anos de luta, ele começou a repensar a validade dessa busca incessante pela igualdade e “atinou pela primeira vez” para a possibilidade de construir “alianças afetivas”, que se apoiam em afetos entre mundos não iguais, onde cada um não perde sua individualidade, conjugando o verbo “mundizar”, que expressa a possibilidade de experimentar outros mundos. E ele cita o exemplo dos países andinos que discutem a refundação da nação a partir de um Estado plurinacional: “A ideia desses Estados nacionais é muito limitada, muito pobre, e a gente tem que ser capaz de atravessar tudo isso e confluir. Quem sabe a presença dos povos indígenas na construção do novo constitucionalismo da América latina, a partir dos Andes, traga outras perspectivas sobre aquilo que nós chamamos de país e de nação? Porque os povos originários têm outras contribuições ao debate, tanto sobre a pólis quanto sobre as ideias de natureza, ecologia e cultura”(p. 89 ). Não tenho maiores informações sobre esse projeto dos povos andinos. Algum de vocês sabe algo a respeito?

Krenak passa a evidenciar as contradições observadas nas democracias. Afirma que a democracia precisa ser construída cotidianamente, pois está sujeita a todo tipo de ataque e a sociedade deve estar atenta para os desvirtuamentos que podem ocorrer. Cita os exemplos dos Estados Unidos e do Brasil. No primeiro caso, chama atenção para o absurdo de um negro ser asfixiado em plena rua por um policial branco enquanto o país exporta democracia para o Líbano, Iraque, Irã e Afeganistão. No Brasil, nos anos 2020, vemos os símbolos nacionais serem “apreendidos por pessoas tão autoritárias que impedem os outros compartilharem deles”( p. 87 ). Seria o caso de uma privatização dos símbolos pátrios?, ele pergunta( p. 88 ).

Em “O coração no ritmo da Terra”, Krenak faz considerações sobre o processo educativo. Ele observa que educadores de diferentes culturas procuram moldar as pessoas, enquanto os povos originários buscam usar técnicas ligadas à produção das pessoas, o que é muito diferente porque considera “que todos nós temos uma transcendência e, ao chegarmos ao mundo, já somos – o ser é a essência de tudo. As outras habilidades que podemos adquirir, como possuir coisas, seguir uma profissão, governar o mundo, são camadas que você acrescenta à perspectiva de um ser que já existe”( p. 94 ).

Krenak acentua que nós podemos apenas imaginar o futuro e acabamos construindo um mundo com uma única narrativa e, ainda mais grave, desde a modernidade as pessoas são inseridas nesse mundo de forma competitiva. Chama atenção para o fato de que o período da infância estar sendo encurtado e que “se não tomarmos cuidado, a próxima geração vai ter suprimida de vez a experiência da infância como esse lugar fantástico – de seres ainda pousando na Terra – e será introduzida de cara em um mundo em disputa”( p. 99 ).

Krenak destaca a importância dos primeiros sete anos de vida, quando ainda somos meio anjos e meio humanos, quando não deveríamos sofrer nenhuma moldagem: “Penso nas palavras “molde”, “forma”, “formar”, “formatar” etc., e que aplicar esses conceitos a pessoas no primeiro momento da vida, quando são seres inventivos e cheios de subjetividade, é uma violência muito grande. No lugar de produzir um futuro, a gente deveria recepcionar essa inventividade que chega através das novas pessoas. As crianças, em qualquer cultura, são portadoras de boas novas. Em vez de serem pensadas como embalagens vazias que precisam ser preenchidas, entupidas de informação, deveríamos considerar que dali emerge uma criatividade e uma subjetividade capazes de inventar outros mundos – o que é muito mais interessante do que inventar futuros”( pp. 99-100 ).

Krenak destaca a importância da criança ser colocada em contato com a natureza, socializando não somente com seres humanos, mas também com animais, árvores, montanhas, rios, a Terra enfim. Acusa as famílias ocidentais de supervalorizarem o sistema de educação e desde cedo levarem as crianças a pensarem que precisam “alcançar um patamar de excelência e ocupar lugares de destaque, pois no topo do pódio só cabe um”( p. 105 ). Cita a campanha de Greta Thumberg que instiga os jovens contra o mundo adulto, buscando libertar-se das amarras impostas por um sistema educacional sufocante. E afirma: “A escolha de um outro mundo pode ser feita aqui e agora e será feita pelas crianças, não pelos adultos”( p. 106 ).

No mundo ocidental, a sala de aula já constitui uma prova da intenção de formatar as pessoas, pois reúne grupos de crianças da mesma faixa etária, sendo instruídas por um adulto que as leva a se alinharem a um determinado propósito marcado geralmente pela busca da alfabetização, longe do meio ambiente e valorizando uma vida sanitária( nada de mexer na terra e se sujar ). Krenak pergunta: por que não deixarmos que as crianças passem mais tempo para si mesmas, descubram coisas, ao invés de serem formatadas? Por que não usar a técnica da meditação nas escolas? Por que não incentivar as crianças a invocarem os ancestrais como recomenda o Papa Francisco? Por que limitar a escola a um prédio, uma sala de aula? Por que não ter aulas embaixo de árvores?

Ele destaca que algumas escolas indígenas estão buscando reconfigurar o sentido da própria educação: “Essas escolas não são plataformas de lançamentos de meninos, mas lugar para eles estarem. Nós, que persistimos em uma experiência coletiva, não educamos crianças para que elas sejam campeãs em alguma coisa, mas para serem companheiras umas das outras. Não almejamos, por exemplo, que virem chefes. A gente não treina chefes.[…] A eventual liderança de uma criança será resultado da experiência diária de colaboração com os outros, não de concorrência”( p. 115 ).

A educação deveria trabalhar para que as pessoas sintam que não estão sozinhas no mundo e se percebam como parte de um sujeito coletivo.

Outro aspecto levantado por Krenak é que a educação indígena leva as crianças, e consequentemente os adultos, a valorizarem a velhice e a não terem medo de envelhecer como ocorre nas culturas ocidentais. Ele diz: “…nossas crianças[…] não veem a velhice como uma ameaça, mas como um lugar almejado, de conhecimento…”( p. 117 ).

E conclui: “As crianças indígenas não são educadas, mas orientadas. Não aprendem a ser vencedoras, pois para uns vencerem outros precisam perder. Aprendem a partilhar o lugar onde vivem e o que têm para comer. Têm o exemplo de uma vida em que o indivíduo conta menos que o coletivo.[…] O que nossas crianças aprendem desde cedo é a colocar o coração no ritmo da terra”( pp.117-118 ).

Realmente essas colocações nos fazem pensar e perceber que precisamos rever muitas de nossas propostas educacionais.

- Teresinha Aparecida Del Fiorentino tem Pós-Graduação em Metodologia e Teoria da História pela Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da USP(1969), Mestrado em História pela Faculdade de Folosofia, Letras e Ciências Himanas da USP (1976), Doutorado em Ciências Humanas pela Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da USP (1978). Obras publicadas: Utopia e realidade: o Brasil no começo do século XX, Editora Cultrix, São Paulo, 1979; Prosa de ficção em São Paulo: produção e consumo, Editora Hucitec, 1982; História da América através de textos, Editora Contexto 1989 (obra feita em conjunto com Jaime Pinsky e outros). A produção e o consumo da Prosa de ficção em São Paulo (1900-1922 ), Revista de História v. LVI, n. 112, 1977, pp. 499-515.

Want to join the Reading Group “Paulo Freire: Extension or Communication” supported by CLAREC and Universidade Emancipa? Depending on the number of registrants, the sessions will be in English, Portuguese or Spanish. We will meet online via Zoom on Mondays, October 10th and 24th, 18:00 UK BST (14:00 Brazil/Chile). For more information and registration, please visit: https://bit.ly/freireconference

Want to join the “Ailton Krenak Reading Group” supported by CLAREC and Universidade Emancipa? The dialogues are in Portuguese or Spanish and take place every fortnight on Fridays. For more information, please visit: https://bit.ly/akrenak

Want to join the “bell hooks Reading Group” supported by CLAREC and Universidade Emancipa? The dialogues are in Portuguese or Spanish and take place every fortnight on Fridays. For more information, please visit: bit.ly/bell_grupo

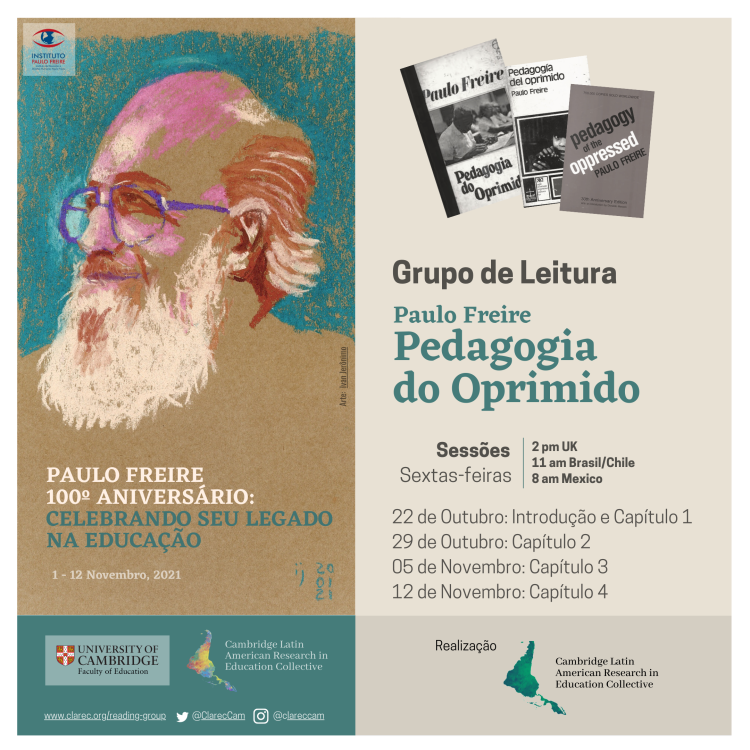

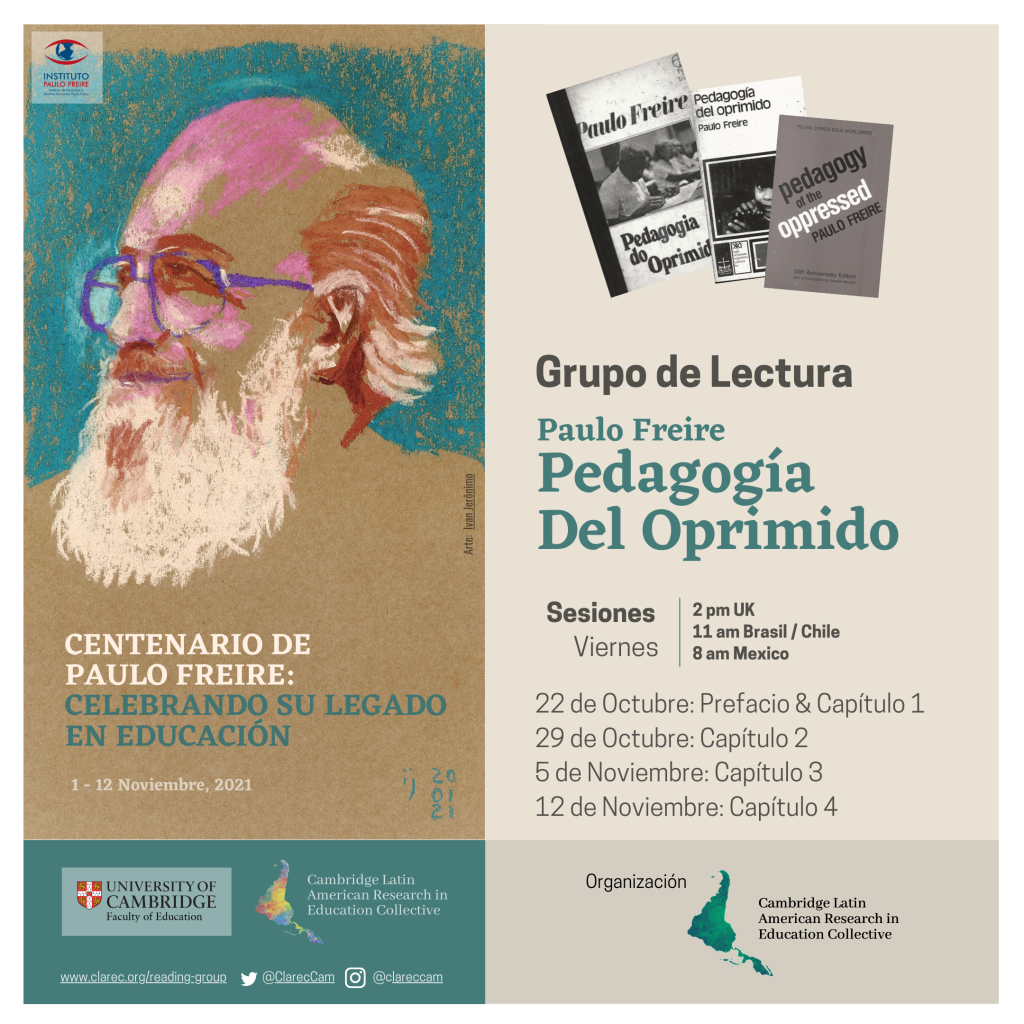

CLAREC Reading Group Michaelmas Term 2021: “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” (Freire, 1968)

…We educate one another in communion in the context of living in this world.

Following our previous reading group on ‘The idea of Latin America’, for this Michaelmas term we welcome everyone to reflect, discuss and reinvent collectively some of the ideas of Paulo Freire, one of the greatest thinkers in education. This initiative is part of the Paulo Freire 100th Anniversary: Celebrating his legacy in education, a series of academic and cultural activities organized by CLAREC in partnership with the Faculty of Education and partner institutions.

To sign up for the group please register here and feel free to contact us on clarec.cam.edu@gmail.com with any questions.

General Guidelines:

- The group will meet in Zoom and in-person at the Faculty of Education (DMB – GS5) on Fridays at 2pm UK time (11am Chile-Brazil/ 8am Mexico).

- The online rooms will be conducted in English; and in Portuguese and Spanish depending on the interest of the registrants. The in-person reading group will be conducted only in English, at the Faculty of Education at Cambridge.

- The sessions will not be video recorded; however, we aim to take notes of the discussions which will be possibly shared on our website.

- We encourage participants to join all or most of the sessions and read the assigned chapter, although if you cannot commit to all of them or read the full text, you are still welcome to join.

- The online and physical rooms will be limited to a maximum of 15 people to promote greater engagement.

- Please contact us at clarec.cam.edu@gmail.com if you want to participate but have no access to the book.

- To subscribe to the reading group and receive further information, please fill in this form. We will share Zoom details and Room number closer to the date.

About the Book: Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1968) constitutes one of the most prominent works of Paulo Freire and a foundational text for the field of critical pedagogies. In this book, Freire problematizes the relations of domination that characterizes conventional education and discusses the possibilities for liberation and emancipation through education. It proposes not only an educational theory but also ontological and epistemological perspectives about humankind and the world.

All Sessions:

| Session | Date | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Friday – October 22nd | Preface & Chapter 1 |

| 2 | Friday – October 29th | Chapter 2 |

| 3 | Friday – November 5th | Chapter 3 |

| 4 | Friday – November 12th | Chapter 4 |

Questions and comments

CLAREC Reading Group Lent Term 2021

CLAREC is inaugurating a reading group format where we invite you to read, reflect and discuss together following a sentirpensar / sensingthinking approach. The reading group is open to everyone and we encourage you to bring all your ideas, experiences, questions, and propositions to collectively build understanding and knowledge.

The group will meet in Zoom every two weeks on Fridays at 2 pm – 3 pm UK time (11 am Chile-Brazil/ 8 am Mexico). The sessions will not be video recorded; however, we aim to take notes of the discussions which will be possibly shared on our website. We encourage participants to join all or most of the sessions and read the assigned chapter, although if you cannot commit to all of them or read the full text, you are still welcome to join.

We are starting in Lent Term with the book “The idea of Latin America” (2005) by Walter Mignolo. Prof. Mignolo is a key thinker of Latin American Decolonial Theory and in the book, he discusses how the notion of Latin America came to be through colonialism and nation-state building processes. The group will be conducted in English, however, if preferred, a Spanish edition of the book is available. If you are in Cambridge, you would be able to get a printed copy of the book at the Library. Otherwise, please contact us if you want to participate but have no access to the book. We will share Zoom details closer to the date.

To sign up for the group please send an email to clarec.cam.edu@gmail.com and feel free to contact us with any questions. See the Term Card attached for more information. The sessions will be as follow:

| Session | Date | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Friday 22nd January | Preface: Uncoupling the Name and the Reference |

| 2 | Friday 5th February | Chapter 1: The Americas, Christian Expansion, and the Modern/Colonial Foundation of Racism |

| 3 | Friday 19th February | Chapter 2: “Latin” America and the First Reordering of the Modern/Colonial World |

| 4 | Friday 5th March | Chapter 3: After “Latin” America: The Colonial Wound and the Epistemic Geo-/Body-Political Shift |

| 5 | Friday 19th March | Postface: After “America” |

About sentirpensar (or sensingthinking): this approach refers to a way of being and knowing that combines the mind and the heart. The concept of sentipensantes come from the inhabitants of the Depresión Momposina region of Colombia who coined it to express their mode of experiencing life. The concept was brought into social science by Colombian sociologist Orlando Fals Borda and widely popularized by Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano. Sentirpensar as a way of knowing has been used by grassroots collectives and decolonial authors to name a practice of knowing that differs from Western Enlightenment tradition which favours the reason over sensing or feeling. We want to bring this idea to our reading group to propose a space that allows discussions involving all our senses in an attempt to break through rigid modes of knowing in academia. In the video below in Spanish, Fals Borda explains the origins of the concept.

Notes

Session 1: Preface

“You can tell the story of the world in as many ways as you wish, from the perspective of modernity, and never pay any attention to the perspective from coloniality”

(Mignolo, 2005, p. xi)

The first part of the session was dedicated to introducing the group and the participants. The conveners shared some ideas about the aims of the reading group for this term, focusing on the need of de-centering knowledge in Higher Education spaces, such as Cambridge, and making space for non-Eurocentric perspectives to be allowed in the discussions. We situated the group from a decolonising perspective which is not rhetorical but rooted in action, in this case, through organizing collective learning as a form of transforming our academic context. We briefly contextualised the contributions of the modernity/coloniality group and Mignolo’s work, considering also the critiques to decolonial work being done in elite Western universities as marginalized voices are still leave outside these centres of power. Finally, we shared a video explaining the idea of sensing/thinking and how it could be taken to a research practice which assume itself as political. We position ourselves working towards transforming our daily academic spaces trough unlearning and questioning our own practices of knowledge production.

During the second part of the meeting, we discussed the Preface of the book using small groups and a final plenary to share ideas. Many interesting ideas came up, some of the main points were the following:

- Questioning our own ideas of Latin America as they are mostly based on the construct created by the West through colonization. Multiple identities exist in the framework of Latin America and different histories are bounded in that idea.

- Our ideas of Latin America might be shaped by experience, for example, by the same experience of going abroad to study or work and being confront with a need for classification or categorization of our identity, as is often the case in institutional contexts. Also, the experience of growing up in certain place, schooling experiences of teaching focusing on Western perspectives and ideas coming from studies of international development.

- The mobile boundaries of belonging that are shaped geographically, culturally and politically, including and excluding territories and people according to certain circumstances. Some cases that were discusses were the Caribbean; Puerto Rico as being under the domination of the U.S.; and Mauritius as an interesting case of a territory formally part of Africa but culturally identified with Asia. Also, the identities that are more invisibilized such us indigenous identities, and how us as part of an intellectual group need to acknowledge the groups which are not part of our conversation in here.

- The colonization of the mind in Latin America, mostly exemplifies through the narratives taught in school, a deeply Westernized education and a lack of criticality to challenge Western hegemonic views. Coloniality is also expressed through ideas of what is to be civilized. We need to use spaces like this reading group to unlearn and critically thing about what we have been taught.

- Paradoxically, even when we come to Western universities from Latin America having been educated under Westernized knowledge in top universities in Latin America, there is a knowledge hierarchy that position ourselves and our knowledge in a lower position and limited the spaces we can occupy in the Global North.

- How can we find paths that avoid binary thinking and hegemonic perspective about the South? What are the alternatives to move away from thinking within the modernity/coloniality framework but without getting into a new binary thinking? Open up space to dialogue, as there cannot be a dialogue is the monologue is still on.

Session 2: Chapter 1 – The Americas, Christian Expansion, and the Modern/Colonial Foundation of Racism

“[…] knowledge is always geo-historically and geo-politically located across the epistemic colonial difference. For that reason, the geo-politics of knowledge is the necessary perspective to dispel the Eurocentric assumption that valid and legitimate knowledge shall be sanctioned by Western standards, in ways similar to those in which the World Bank and the IMF sanction the legitimacy of economic projects around the world.”

(Mignolo, 2005, p. 43)

The second session of the reading group started with a brief recapitulation of the previous meeting and some thoughts on the context the book was written 15 years ago, considering that global geopolitics have changed in some ways from that point to the present. We then move on to discuss some of the key concepts introduced in Chapter 1 that are at the base of Decolonial thought, in order to generate a common ground of understanding.

- The discussion foregrounded the general feeling that when faced with the concepts exposed in the book, we realized that we are all unlearning (or de-constructing) previous knowledge about power balances and ways of being around the world as well as the role of coloniality on this and how it affects our own lives, careers, and understanding of the world. Basically, the process of decolonising ourselves.

- We abandon the expectation that is possible to discuss what Latin America is as a unity because that very form of seeing Latin America as unity is referred to a colonial and universalistic paradigm, a type of generalization that emerges from Western thought.

- In relation to the construction of Latin America as a unity, is interesting to discuss the case of Brazil, because usually Brazilians see themselves as separated from the rest of Latin America, not being fully part of it, and it will be interesting to explore these differentiations that happen inside the “idea” of Latin America.

- Understanding modernity/coloniality as concepts that are relational and tied up together historically and temporally. Colonialism referring to the historical events of imperialism appropriating land and coloniality referring to the logic of domination that still exists, an ongoing imperialism. The structures that still remain and influence all aspects of how we think and live. Following Quijano, coloniality refers to the open wound that still exists even if imperial power is not formally present.

- Colonial logics have also evolved as the geopolitics of power around the world shift, however, imperialism is not really over, for example, the case of Puerto Rico and neocolonialism through capitalist and finance system. Awareness of not seen colonialism as a linear process that is over and will not come back.

- The strong role of religion and Christianity in colonialism for the case of Latin America in comparison with other former colonies where religion does not seem to be imposed so strongly or have not perdured in the same form. How nowadays in Brazil, for example, Christianity is connected with the emergence of neoconservatives and has historically supported the maintenance of western hegemonic views, with the Catholic church actively silencing Theology of Liberation. Additionally, in Latin America, the connection between Christianity and the foundations of extractivist capitalism is based on the idea of their right of taking possession, which translated into exploitation. This quote by E. Galeano was shared: “They came. They had the Bible and we had the land. And they said to us, ‘Close your eyes and pray. And when we opened our eyes, they had the earth and we had the Bible.”

- Decoloniality is a political and epistemological project, there is no one way of doing decoloniality, but it does comprise o shift in paradigms. We discuss postmodernity, for example, as an alternative that is actually part of the same paradigm of Western interpretation. Decoloniality proposed the pluriverse, in opposition to binary thinking, meaning the possible coexistence of different paradigms at the same time. A turn from the universal idea of modernity to a pluniversality, which is a more collaborative and hopeful understanding of the future, the conviviality of many different perspectives (perspectives as differing from interpretations).

- The coexistence of different perspectives is not a quest for new imperialism to emerge through relativism but a shift in the paradigm of the need for appropriation and conquering, to dialogue. Is not either to go back to a lost past but building up from different starting points of that of modernity, from other knowledges that have been left out from the conversation.

- We closed the session with some big questions about the possible futures: how we can get there after this exploration of how we got here? Learning and understanding about the complexity of coloniality seem like a very small first step but at least it opens up the possibility of looking at many different worlds.

- Because this is not past history, is happening, what we do in practice, in our communities? How we can “action” this knowledge we are getting into in the spaces we occupied, to challenge coloniality? Should we strive to create a pluriversity instead of a university? How we can reach border thinking, how we can get to that point where we see things in a different way? Is border thinking related to an experience of subordination and oppression or can we all practice this?

Session 3: Chapter 2 – “Latin” America and the First Reordering of

the Modern/Colonial World

“Decolonization at this point, as well as in the second wave post-World War II, meant political and, in a less clear way, economic decolonization – but not epistemic. The theological and secular frames of mind in which political theory and political economy had been historically grounded were never questioned. […] Colonialism should have been the key ideology targeted by decolonial projects. However, in the first wave of so-called decolonization, colonialism as ideology was not dismantled, as the goal was to gain ostensible independence from the empire. There was a change of hands as Creoles became the state and economic elite, but the logic of coloniality remained in place”

(Mignolo, 2005, p.85-86)

• The third session of the reading group started, as always, reflecting on the discussion of our last meeting, especially concerning how we can put decolonization into action. Part of the efforts our collective in relation to this is showcasing different perspectives, aesthetics, and experiences. A key issue is decolonising ourselves to be able to value other types of knowing and being as well as respecting the multiplicity of worldviews.

• Starting chapter 3, Walter Mignolo talks about Pachakuti, a term from Quecha people, inhabitants of the Andean region, that means a time of change in the orders of things, central for the understanding of Quechua epistemology. Later, at the end of the chapter, the author goes back to the idea of Pachakuti, explaining that the erasure of Indigenous and Afro populations by the idea of Latinidad has been challenged in recent decades by Indigenous and Afro social movements reclaiming political space. In order to acknowledge the usefulness of Indigenous epistemologies to understand these historical processes (as the author is, for example, using a Quechua term) and also to share a moment of sensorial experience, we listen together the poem Kawsaq, by Quechua poet Irma Álvarez Ccoscco:

• Two main points came out in the discussion of the chapter. First, the role of the Creole elites, or Criollos, in maintaining the colonial cultural power in Latin America, through trying to be “like them” (assimilation to Europeans) and maintaining the epistemological hegemony of European thought at the same time than actively silencing Indigenous and Afro epistemologies. The second point discussed was possible knowledges that do not depart from modernity and the foregrounding of Indigenous knowledge as alternative perspectives but also considering some of the dilemmas that arise in relation to belonging and appropriation.

• The internal colonization driven by creoles elites responded to a desire of being alike the colonizer in many senses, and one of them was imposing their power as if they were superior, so they replace the previous power of the colonizer. The decolonization that occurs at this point during the Independence period was political but not epistemic, a type of half-way through decolonization.

• The creole elite aspires to the modernity idea of Europe, but Latin America did not become modern as expected and was caught up in internal colonialism and neo-colonialism, so it was not able to move forward from colonialism either. Internal colonialism and neocolonialism have been changing their strategies, for example, in Brazil from the Catholic church to Evangelism. Schooling has also been a relevant tool used for internal colonialism, mainstream schooling has not allowed different epistemologies, it has followed the idea of modernity as a goal and silencing local knowledges.

• This process has some differences across countries, it might be possible to identify different paths of decolonization in Latin America and would be worth exploring where those differences came from. However, colonial ideas seem to be very strong everywhere, and even many times we see social movements inspired by European thinkers. For example, the case of Marxist ideas that in many cases have not been able to fully address Latin American issues, especially regarding the differences in stratification by race and class. Although the book mentions some cases from the last two decades in Latin America as examples of attempts to use political ideas contextually grounded, many of them have not been able to sustain power positions. These movements still clash with the modernity aspirations of the elite and end up been sabotaged by it.

• The difficulty of thinking and developing alternatives ways to modernity because we are inside the colonial paradigm, but in this sense, Indigenous and Afro epistemologies in Latin America represent alternatives perspectives. Is not about idealizing them or a past era before colonization but allowing those knowledges that were erased to be considered in the conversation. It might also be interesting to think about indigenous knowledge beyond language, through artwork, music, nature, for example (going back to the idea of sentipensantes).

• The power of knowledge seems to be tightly tied with languages. For example, in schooling, imperial languages are preferred or more relevant, there is a language stratification. Indigenous languages are introduced into schooling mostly as part of intercultural programs and mostly absent in Higher Education (although we commented on the case of Indigenous Higher Education projects in Bolivia, for example). The debate about Indigenous knowledge in institutional (and Western?) educational settings posed questions about belonging in a complex mestizo society and there are several aspects to consider regarding respecting those who own that knowledge, avoiding appropriation or extractivist practices, and the debate about schooling seen as a form of supporting coloniality.

• The idea of a unity constructed through Latinidad has also tried to impose one way of thinking, doing, and being throughout different cultures in Latin America but, on the contrary, decolonization is not about choosing one way of doing things and then “scaling it up” to all Latin America, because this is the imperialist way of thinking. Is not about discussing which is the best universal alternative but accepting that different alternatives should coexist.

Session 4: Chapter 3 – After “Latin” America: The Colonial Wound and the Epistemic Geo-/Body-Political Shift

“The key issue here is the emergence of a new kind of knowledge that responds to the needs of the damnés (the wretched of the earth, in the expression of Frantz Fanon). They are the subjects who are formed by today’s colonial wound, the dominant conception of life in which a growing sector of humanity become commodities (like slaves in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries) or, in the worst possible conditions, expendable lives. The pain, humiliation, and anger of the continuous reproduction of the colonial wound generate radical political pro¬jects, new types of knowledge, and social movements”

(Mignolo, 2005, p. 97-98)

• We start the meeting by summarizing some of the points of our previous meeting, especially about the role of Indigenous knowledge and who is allowed to use/access it. In this chapter, the author touch on this issue as is a common question in today’s progressive politics. The risk here is essentializing Indigenous groups and Indigenous knowledge and confined it to the space of cultural identity, in the sense of identity politics, instead of seeing Indigenous knowledge as a broader political project that can be supported by anyone. This is also linked with the conversation about how categorization confined people to certain identities acting many times toward exclusion, as in the case of the Latino category that most of the time does not acknowledge Indigenous and black populations.

• The role of institutions, especially academia, in following the path of co-existence instead of newness. The paradigm of newness, based upon the perspective of European conquers thinking that they were discovering and starting something new, is opposed to the paradigm of co-existence, that recognizes the existence of different epistemologies, taking the stance or the perspective from the colonial wound. The chapter discusses the decolonization of knowledge in relation to social movements but does not explicitly addressed the issue of decolonisation of academia.

• A key issue in decolonising academia is questioning our positionality and our role in the configuration of knowledge, even in teaching students (as pointed out, for example, by Boaventura de Sousa Santos in “Knowledge born in the struggle”). However, we contrast Santos’ idea of the Epistemicide (some knowledges being silenced and erased) with what Mignolo points out about the body-politics of knowledge: knowledge cannot be totally erased because it remains in the body memory as part of the subjects, even when they are forced to not put it in practice. This might explain the optimism we see in this chapter in relation to social movements in Latin America.

• We have a responsibility to question the structure embedded in our institution, the paradigm of modernity that is so present also in University in the Global South. Critiquing the institution we are part of is an uncomfortable position that goes together with ethical dilemmas of the work we are doing in these institutions, however, for sure these critiques will enrich environment the environment of higher education. Decolonial critiques and decolonial research have a role in creating spaces for other perspectives in higher education.

• At the level of institutions, it is a challenge to see the alternatives and possibilities for decolonising, how to take action in this regard. There is no one way or a model but is easier to see it from the small steps we can take in everyday work and from there strive for deeper change, everyone considering their own possibilities to do this. We took the example of efforts for decolonising the curriculum in the university and also reading groups such as this one. Decolonising the curriculum in the sense of adding Southern authors to the reading lists are relevant efforts but after this step is important to take into account how this is implemented, if it is just a token name in the reading list or if real engagement occurs discussing all authors, Western and Southern, at the same level. Many times, is problematic how Southern authors are legitimized into the curriculum only when discussed by Western authors as a form of legitimizing them as worth of being part of the Western University.

• The role of dialogue appears here again as an essential part of the decolonising work in academia, and we linked it with Paulo Freire’s work as he proposed a cultural circle of the denunciation of the injustices and then the announcement of the possibilities (which also can be seen in relation to transformative justice). These two steps can help to move forward the inclusion of new epistemologies in academic spaces, using dialogue to connect different epistemologies, instead of antagonizing them.

• Dialogue seems somehow difficult in academia, as contradictory as this might look, because is common that people cling to their ideas too strongly as they are an essential part of their research and their identity as researchers. Usually when people become experts in their field is even harder to challenge their position or perspective. There is a need for practicing humility and vulnerability in academia, accepting that there might be different perspectives than our own and that they are also valid and maybe even more adequate than ours for a certain issue; we need to look at other perspectives and establish a dialogue.

A couple of readings recommended during the session:

- Blaser, M., Briones, C., Burman, A., Escobar, A., Green, L., Holbraad, M., & Blaser, M. (2013). Ontological conflicts and the stories of peoples in spite of Europe: Toward a conversation on political ontology. Current Anthropology, 54(5).

- de Oliveira Andreotti, V., Stein, S., Ahenakew, C., & Hunt, D. (2015). Mapping interpretations of decolonization in the context of higher education. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 4(1).

Session 5: Postface – “After America”

“The “idea” of America is not only a reference to a place; above all, it operates on the assumed power and privilege of enunciation that makes it possible to transform an invented idea into “reality.” This fact has been overlooked as if the continent already had its name inscribed naturally on the face of the earth. “America” did not name itself as such, despite the invisibility of the power relations behind its nomenclature. At work here is the coloniality of knowledge, which appropriates meaning just as the coloniality of power takes authority, appropriates land, and exploits labor”

(Mignolo, 2005, p. 151-152)

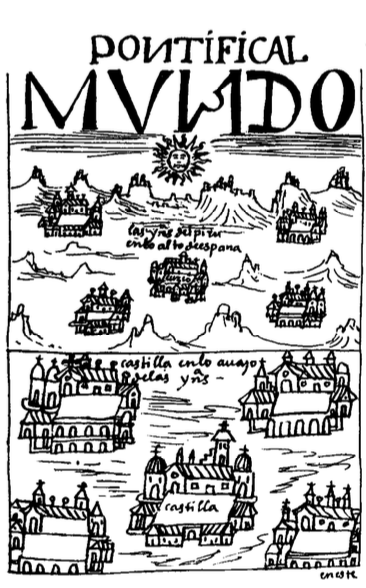

- The last session was devoted to the Postaface of the book and final reflections on book. We started commenting the two images proposed by Mignolo to point out to the difference between changing the terms of the conversation and not only the content. This implies a change on how to see the world but not only putting what exist now upside down (the inverted map by Joaquin Torres-García) but offering a new view of the world (the Pontifical Mundo by Waman Puma). Waman Puma’s map shows the coexistence of the two worlds already existing, the coexistence of epistemologies, which is a different logic of what the European colonization imposed in trying to erase the existence of epistemologies of the Americas.

- Epistemologies of the South are diverse too, is important not to fall into a homogenization idea, which would also be a colonization mechanism that classifies knowledge in binaries.

- The idea of coexistence of epistemologies is in some ways hard to understand for us because we might not have yet the terms to understand this, we are so used to a world where the Eurocentric view is dominant, or where there is a dominant view or epistemology, that thinking in coexistence is challenging to imagining. We need to move to a polycentric approach. Although we have to recognize the knowledge that we are putting in coexistence still existence in the ruins of colonialism and so there will be probably power dynamics and imbalances at play. However, in a coexistence of epistemologies, this could be resolve in other ways than oppressing and erasing difference.

- The coexistence of knowledge deviates of idea of neutral knowledge but also relativism and must be understand in relation of what Mignolo calls the body-politics and geo-politics of knowledge, in the sense that knowledge is situated and imbricated in experience. Feminist theory has extensively addressed this issue (see for example standpoint view).

- We also want to avoid falling into the fictional tension of between using Western or Southern authors in the sense that the important issue is to use the knowledge that is relevant for certain problem and thinking about it in the specific context. We discuss the example of Marxism in Latin America. Hardt and Negri idea of the multitude as different identities that work towards some common goal was also mentioned as relevant to the idea of coexistence.

- Understanding coexistence and our position in it is also challenging for us Latin Americans because we are part of the colonial history in the sense that Paulo Freire describes as the oppressed who host the oppressor in themselves, participating in the liberation and having the colonialist in ourselves at the same time. This is part of the colonial wound and very hard to unpack.

- The idea of the colonial wound also talks to the need of sitting in with the grief of the wounds left by colonialism on us and how the healing and the care can happened now.

En unas pocas centurias, the future will belong to the mestiza. Because the future depends on the breaking down of paradigms, it depends on the straddling of two or more cultures. By creating a new mythos – that is, a change in the way we perceive reality, the way we see ourselves, and the ways we behave – la mestiza creates a new consciousness.

Gloria Anzaldúa (from Mignolo, 2005, p. 162)

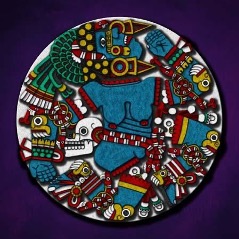

- The postface ends with a powerful quote from Gloria Anzaldúa, and it was bring to the group that Gloria Anzaldúa uses in her book “Light in the Dark” (“Luz en lo Oscuro”), the metaphorical image of Coyolxauhqui stone to explain the colonial wound and the re-existence.

- We close the meeting and the reading group reflecting about consciousness, how trough the reading of the book we have come to question and interrogates many assumptions and open up many more questions. How these questions can translate into resistance and new practices in academia in many aspects, for example, how we approach assessing and evaluation of knowledge and finally how we can bring into academia our vulnerability, senses, emotions and making the space for knowledge from experience being brought into our work, acknowledging ourself as complex humans beings.

You can watch below “The Decolonial Epistemic Turn and The Idea of Latin America – A conversation with Prof. W. Mignolo” – a CLAREC seminar that took place on April 26, 2021 which explores issues discussed during the reading group. See the Q&A and chat of this event here.

Participants of the reading group:

The notes from the reading group express the collective reflections of the participants listed below:

| Consuelo Béjares | University of Cambridge | Faculty of Education (CLAREC member) | PhD Student |

| Alexandre da Trindade | University of Cambridge | Faculty of Education (CLAREC member) | PhD Student |

| Tiffeny R Jimenez | National Louis University | Faculty of Community Psychology | Associate Professor |

| Haira Gandolfi | University of Cambridge | Faculty of Education | Lecturer |

| Carolyn Smith | University of Cambridge | Department of Geography | PhD Student |

| Adam Barton | University of Cambridge | Faculty of Education | PhD Student |

| Anna Corrigan | Univeristy of Cambridge | Centre of Latin American Studies | PhD Student |

| Paula Castro | Univeristy of Cambridge | Faculty of Education (CLAREC member) | PhD Student |

| Gibson Zucca da Silva | University of East Anglia | Faculty of Education and Lifelong Learning | PhD Student |

| Franciszek Krawczyk | Adam Mickiewicz University | Faculty of Philosophy | PhD Student |

Questions and comments

Hello all! If you are attending our seminar on Monday 26th of April “The Decolonial Epistemic Turn and The Idea of Latin America – A conversation with Prof. Walter Mignolo”, you can post here your questions and comments to be added to the Q&A. We are looking forward to having your thoughts. CLAREC team.

Deixe aqui sua reflexão

LikeLike

please send the uplinks professor martz and mingolo along with review questions thank you

LikeLike

Thank you everyone for coming and contributing to the discussion in the first session! If you have more thoughts about the first meeting or first impressions on Chapter 1, feel free to comment here.

For those who read in Spanish (sadly is not in English) and want to dig in a little more, I recommend this interview where Mignolo talks about the book, addressing some interesting critiques about it: Lastra, Antonio (2008). Walter Mignolo y la idea de América Latina. Un intercambio de opiniones. Tabula Rasa, No.9: 285-310.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There are many exciting aspects in the preface, but I would highlight how the author explains “dialogue” in this context of modernity, which is actually dependent on coloniality. According to Mignolo, “dialogue” can only exist with decoloniality, which makes me reflect on how a false and corrupted idea of “dialogue” was developed in Latin American regions. In other words, we believe that we dialogue, when in fact we replicate discourses framed on a hegemonic monologue.

LikeLike

Interesting observation – “we replicate discourses framed on a hegemonic monologue” – and I agree that dialogue is only able to engage with the narratives we are able to reach, hold, create. That without the creation of new narratives we are merely replicating or swimming in existing narratives available to us. I am currently teaching a course in Chicago, Illinois, US through a liberation framework, teaching practices of decoloniality through storytelling based on stories of people located around the globe. From a global studies perspective, we puzzle together a study of global histories and learn about the many ways different people engage in practices of decoloniality, or epistemic decolonization. I think an important part of this work is understanding how our mindsets are shaped by varying discourses and an increasing understanding of how ideologies play out in larger narratives we engage with.

LikeLiked by 1 person